A baby born into a world of beliefs has no beliefs of its own until it learns its mother tongue, hears opinions and reasoning of adults, and begins to think accordingly. A fleeting thought comes and goes and is forgotten. But, thoughts repeated, again and again, become belief.

“Beliefs arise through experience. Experience needs previous beliefs and reason to be assimilated, and reason needs experience to be formed. Beliefs, reason and experience, are based upon each other.”

David Mikkelson1

Even a baby elephant can create a belief from experience. It is an elephant’s nature to roam. So, in India at night, a baby elephant born in captivity is chained to a log or tree trunk. At first, it tries to break free and roam but is not yet strong enough to separate itself from the chains or tree. Soon the calf forms a belief that it is weak, it is captive, and stops trying to roam. After the calf grows into an adult and is tied with a thin rope to a small tree that it could easily uproot, the magnificent pachyderm doesn’t even try. It is strong enough to lift or move 600 to 1100 pounds, yet it is conditioned to believe, “I am too weak.”

During my talk at the Women’s Health Conference last weekend, a member of the audience enriched this baby elephant metaphor by telling us that upon sensing the vibrations that precede a tsunami, the latent instincts of elephants can over-ride their conditioning allowing some to break their chains and run to higher ground. In humans, catastrophic events can create an emotional tsunami that forces us to break through conditioned beliefs, languid tedium, or refusal to answer a Call. Crisis can become a timely Call from the goddess of Necessity that rouses the Seeker-within to begin a search for personal freedom (instead of accepting being tied in place by time-worn childhood beliefs).

“Only a small part of you thinks something is impossible, another part, utterly innocent of the odds, doesn’t know it’s impossible.”

–Jean Houston, philosopher and author (from lecture presentation notes)

Many people have achieved the “impossible” because they didn’t know—or believe—it was impossible. Have you ever experienced this phenomenon in your life? In 1939, a young college student at Berkeley, George Bernard Dantzig, did! One night, fearing he would not pass the final exam for a math course, he studied so long that he overslept the morning of the test. When he ran into the classroom several minutes late, he found three equations written on the blackboard. Because he was late, he didn’t hear the instructions. The first two were rather easy to solve, but the third one seemed impossible, but he persisted and worked out an answer. Dantzig turned in his test paper.

Later Dantzig learned students were only asked to do the first two problems. The professor had written the last problem on the board as an example of an equation that mathematicians since Einstein have not been able to solve with success.2 Was it possible for Dantzig to do what no other mathematician had been able to do because he slept in and didn’t know it was “impossible?”

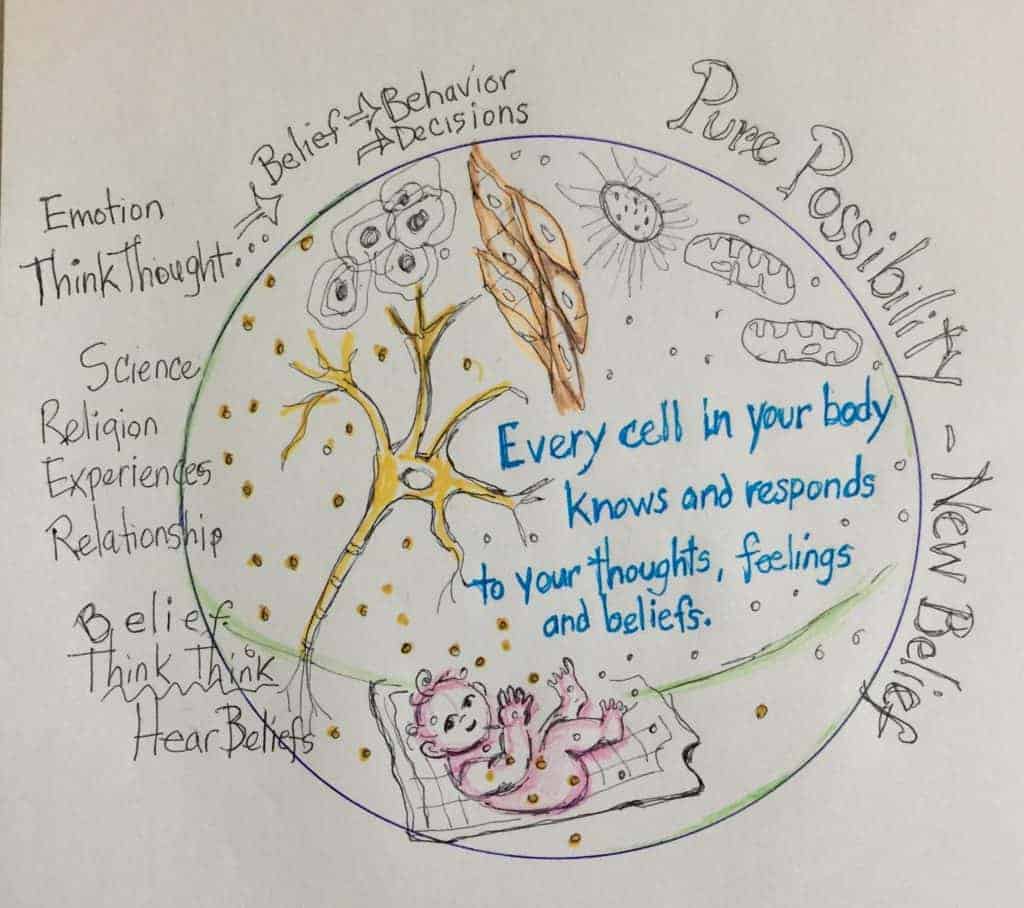

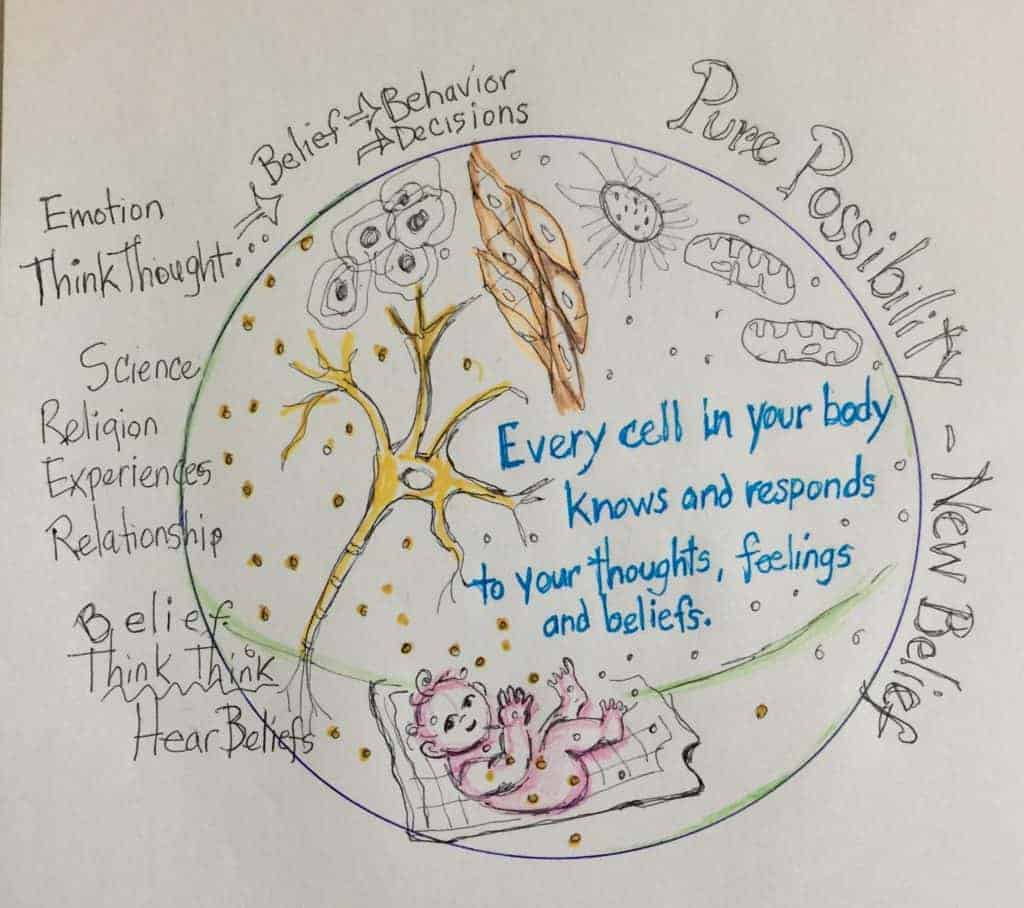

Thoughts and beliefs are not just ideas in your mind. Every cell in your body knows and responds to your thoughts, feelings, and beliefs.

“Everything exists as a Matrix of pure possibilities akin to moldable soft clay… Our beliefs are given shape and form by whatever we desire (consciously or unconsciously). Our beliefs provide the script to write or re-write the code of our reality.”3

In his book, The Biology of Belief, Bruce Lipton recounted a remarkable In his book, The Biology of Belief, Bruce Lipton recounts a remarkable story about the power of belief in healing. In 1951, Dr. Albert Mason, an anesthesiologist who also practiced hypnosis, treated a 15-year old boy for an advanced case of black warts that covered his entire body except for his face and chest; he’d had two failed skin grafts. Mason guided the boy to focus on seeing the skin on his left arm, turning pink and healthy. In other hypnosis sessions, the doctor and boy continued to envision healing of the skin on the rest of his body. Two weeks later, the boy’s skin had healed remarkably. By the time Mason and the patient returned to the referring physician, the surgeon had realized he initially misdiagnosed the boy’s condition; it was not warts, but an incurable, lethal genetic disease called congenital ichthyosis.

After publishing his startling and successful treatment of ichthyosis in the British Medical Journal (1952), other patients suffering from the rare disease consulted Mason for hypnosis, but none experienced a cure. And yet, the boy was healed and went on to live a healthy life. Why?

Consider the role beliefs played in this miraculous cure: Initially, neither Dr. Mason nor the boy knew the skin condition was incurable. Because they both believed the skin condition was just warts and that warts could be cured, they both abided in a morphic field of possibility. Later, when Mason failed to cure ichthyosis in any other patients, he attributed these outcomes to his new knowledge and belief that the skin disease was “incurable;” he admitted he was “only acting” while performing hypnosis.4 It is worthwhile to acknowledge that the patients also knew and believed their “incurable” prognosis.

Beliefs are Stories are Beliefs

We have beliefs about stories and stories about beliefs. Beliefs about cause and effect shape your story about yourself, what is possible, and what is happening—even before it happens. For example, “I think the reason my baby was in the wrong position, and I had to push so long, is because Mercury was in retrograde.” Or, “Mercury is in retrograde, oh dear, this will probably make labor harder.”

“Belief systems are the stories we tell ourselves to define our personal sense of reality. Every human being has a belief system that they utilize, and it is through this mechanism that we individually, “make sense” of the world around us.”

Usó-Doménech, J.L., et.al.5

Events in and of themselves have no inherent meaning. Yet humans seem to be hard-wired to find meaning in their lives, so much so that one of the first questions children ask is, “Why?”

After an unwished-for experience in childbirth, people often ask, “Why me?,” “Why my baby?” Any and every answer reframes the story and creates beliefs that either foster guilt or blame, or that foster self-acceptance. A storyteller seeking meaning to redeem an experience might say, “This happened because I needed a lesson in perseverance.” Sometimes a storyteller turns what happens against herself creating a limiting self-belief such as, “The nurse forgot to come back to check on me because I don’t matter.”

Meaning exists only in mind, not in the world, and not in the story itself. Therefore, if you don’t like the meaning you believe about your birth or life experience–or yourself in regard to it–remember that you invented it so you can change it!

Believe That a Change of Heart is Possible

After giving a talk at an International Cesarean Awareness Network conference (2011) about “The Nine Birth Story Gates” and how a birth story evolves, many people told me their biggest take away was that cesarean birth trauma was not fixed-for-life. They had no idea—or hope—that the meaning a storyteller initially gave their birth story could change and heal. If neither the storyteller nor story-listener know the “map” to healing and have no hope for healing, then their search for the hidden healing may stop too soon. And indeed, reinforce their belief that the wounded story may be the story they carry all their lives–and the one that they repeat and pass on to the next generation.

On the other hand, to the degree a storyteller and story-listener accept that beliefs are relative (not absolutely true), malleable and evolving, is the desired change of heart possible. Expecting to find new meaning does not necessarily make the road to healing easy or quick, but it does provide hope, motivation, and creativity during steady excavation of the story until the hidden healing is discovered.

To the degree the storyteller and story-listener accept that beliefs are not fixed, rather they are malleable and evolving, is the desired change of heart possible. Expecting to find new meaning does not necessarily make the road to healing easy or quick, but it provides hope, motivation, and creativity during the patient excavation of the story until the hidden healing is discovered.

Assessing personal beliefs is an often overlooked but fundamental Task of Preparation for childbirth. Beliefs become filters limiting holistic preparation for birth in our culture, for example the belief that by learning about cesarean birth one invites it or creates it. Beliefs more than evidence-based information animate our behavior and decisions. “To say that someone believes something is to say that someone is disposed to behave in certain way under certain conditions.”6 People believe themselves to be rational, and yet at different times we have believed in something that defies logic, or we’ve believed in and trusted someone for which there was no evidence we should, or even when there was evidence to the contrary!

The ongoing inquiry: Which came first, the chicken or the egg? The beliefs or the story? Maybe which came first is less important than knowing that birth stories and beliefs are synonymous, and to understand one, one must understand the other. And this quest becomes an essential cornerstone of our birth story process.

Pam England

Citations

1 David Mikkelson (1996). “The Unsolvable Math Problem.” https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/the-unsolvable-math-problem/

1 Usó-Doménech, J.L., Nescolarde-Selva, J. What are Belief Systems?. Found Sci 21, 147–152 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10699-015-9409-z

2. David Mikkelson (1996). “The Unsolvable Math Problem.” https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/the-unsolvable-math-problem/

3. Sathyanarayana, RaoTS, et.al. (2009). “The Biochemistry of Belief.” Indian Journal of Psychiatry 51:239-41. http://www.indianjpsychiatry.org/text.asp?2009/51/4/239/58285

4. Bruce Lipton (2005). The Biology of Beliefs. Carlsbad, California: Hay House. pp 117-118

5. Usó-Doménech, J.L.,

6. Peter Halligan, Belief and Illness. https://thepsychologist.bps.org.uk/volume-20/edition-6/belief-and-illness