by Pam England

Watch: “Father and Daughter” (the 2000, Oscar-winning short film animation).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Oo4KXZVApsQ

On Father’s Day, I watched M. Dudock de Wit’s “Father and Daughter” several times. The narrative (without dialogue) tells a poignant story of a young girl happily bicycling with her father to the seaside. Then, he rows out to sea alone but does not return; the girl’s perpetual waiting and uncertainty begins. Seasons and years pass. She grows up and grows old, returning again and again to the place where she last saw her father—looking out to sea for a glimpse of him. In just eight minutes, the film’s says so much—yet its ambiguity allows each viewer to interpret its meaning.

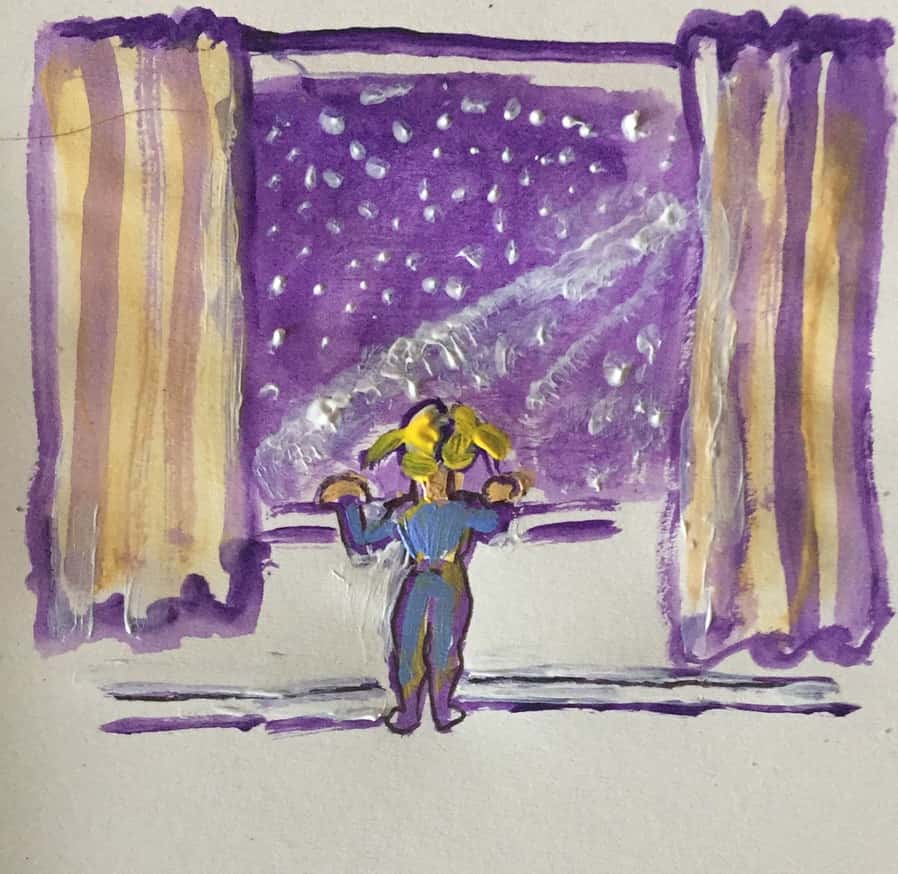

I have often chastised myself for still behaving like a classic Fatherless Daughter in the sixth decade of my life. I have happy memories of my father, sitting on his lap while he told stories of the places he went and what he saw when he drove a truck. He smelled of tobacco and aftershave. One time he brought home baby fox, another time ducklings he found on his travels. He showed me how to plant a garden: we picked raspberries, green beans, and tomatoes. We had a loving relationship. One day when I was six, without explanation, without saying goodbye, my father left suddenly during a blizzard in mid-December. From the living room window, I watched the lights of his car disappear at the end of the snow-packed road. When he didn’t return, I kept vigil in front of that window for a while. My mother (who had borderline personality) completely lost it after he left. I felt alone and afraid. When I realized he was never coming back, I blamed myself, sure that he left because I had been bad or hid his cigarette lighter under my bed (so he wouldn’t smoke and die). How could he leave me alone with my crazy mother? I wondered; maybe he left because of her craziness. I tried so hard to be very good, thinking somehow this would bring him home.

Decades later, from time to time, a ghost memory spontaneously appears in drawings and paintings where it doesn’t “belong:” a little girl in pigtails, head just above the windowsill, looking down a snowy road. Sometimes I leave it; sometimes I paint over it where it still remains, a hidden part of the painting.

THE ARCHETYPAL FATHERLESS DAUGHTER IS PREVALENT IN OUR SOCIETY. One in three women see themselves as a fatherless daughter and struggles with feelings of abandonment.1 In the U.S., 19.5 million children (that’s one in four), live without a father in the home.2 The breakdown by race in 2018: White 18%, Black 55%, and Latino 29%.3 There are many different kinds of families and reasons for fathers not to be in the home including same-sex parents, adoption, artificial insemination, death, and deportation. This blog focuses primarily on fatherlessness through abandonment by desertion (15%), divorce separation (28%), and incarceration (4%).

“Losing a father in childhood forever changes the shape of a daughter’s identity. Not only is her connection to the first and most important man in her life sharply curtailed

—Victoria Secunda, Women and Their Fathers 4

or extinguished,

but all her perceptions, decisions, and future relationships are filtered through

that early, unimaginable, ineffable loss.”

When fathers leave by walking away, incarceration, or divorce, their daughters can begin to experience the fatherless daughter syndrome, “a disorder of the emotional system that leads to repeated dysfunctional relationship decisions, especially in trust and self-worth.”5

However, absence through death, notwithstanding the shock and grief, death comes with “a certainty and a sense of clarity.” Fr. Dave Dwyer observes, “the grieving process of death allows the child to feel included rather than isolated, while the public acceptance of this grief enables the child to mourn their loss at their own pace. A child who has lost a father through death does not have the added burden of dealing with issues of abandonment or rejection.”6

“Children cannot, or may not be able to mourn the loss of their father (i.e., love object) because they will not give up attachment to the love object, hoping he will return. Because they cannot accept loss, they remain in a state of melancholia, a state of being struck. Healthy mourning is time limited, but melancholia involves injury to the ego and therefore persists (Freud, 1917).”7

After a father deserts or leaves the family, the mother is also experiencing loss and abandonment and may not be emotionally capable of supporting her children through grief. Unlike with death where there are funeral rituals, there are no rituals, social acknowledgments, or explanations when a father deserts; the silence invites shame. And celebrations like Father’s Day or Dad’s birthday are awkwardly ignored, but not quite forgotten. Without a supportive environment to mourn, the process of resolving loss is interrupted, and in children, their development is also interrupted at the stage of loss.8 If an alternate paternal figure who loves the daughter does not step in to replace the “object loss,” the young girl may begin to suffer self-esteem and self-worth problems.

The Imprint of a Father’s Abandonment on a Daughter’s Life Long Relationships

A little girl’s first relationship with a man is likely to be her father. Their father-daughter relationship becomes her blueprint for beliefs about what she deserves, should expect, and will choose in her adult relationships, especially with romantic partners. A father who is present, reliable, and caring creates (in a heterosexual daughter) a template for future relationships with men who are respectful, trustworthy, and caring.7 On the other hand, when a father figure fails to see and cherish his daughter (and her mother), when his daughter grows up, she may choose and tolerate poor romantic partners.

In her excellent study, “The Developmental Effects on the Daughter of an Absent Father,” Carlee Castetter found that while both genders may experience detrimental consequences from growing up fatherless, the lifelong effects negatively affect women differently and more drastically.8 For example, girls define themselves based on the quality of their relationships with family and friends. And because they develop their identities through relationships, the absence of a relationship with their father often makes them feel incomplete or unworthy as an individual. They are more likely to internalize feelings of rejection and abandonment and suffer from anxiety and depression than boys. In contrast, boys build their identities through autonomy and independence,9 and are more likely to act out after divorce or abandonment, making others more aware that they’re affected by the abandonment.10 Adolescent teen boys who live with their dads are less likely to carry guns or deal drugs.11

Assumptions & Self-Beliefs of Fatherless Daughters

Some girls (6%) miss a father they never knew.

~Laura

“My father left when I was a year old. He never visited so I didn’t know him, and yet I missed him

and wondered if he ever thought about me.”

The loss of a father at any age has a profound effect on his children: their age, stage of development, and the absence or presence of an alternative paternal figure influence how the separation will affect the child. (Read O’Dwyer, 2017.)12 Often, a father’s sudden absence leaves an emptiness in the daughter filled with loneliness, sadness, and, not knowing if or when he will return, she develops a longing for his return—because his choosing to be in touch or return would mean that she matters—to him. If he does not return, the daughter identifies as a fatherless daughter and makes agreements about her self-worth, relationships, and men:

My father left me and forgot about me; “I don’t matter;

I am not loveable.”

My father did not see me; “I am invisible.”

“I am unchosen, not wanted, unworthy of love.”

“No one knows me for who I am.”

“No matter how much I love or give, he will leave me (eventually).”

Persistent Agreements about Earnings and Financial Security

After walking away or divorce, the other parent’s income alone is often insufficient to support a family (especially when the father does not provide child support). When children whose fathers are absent grow up in homes ridden with financial struggle or poverty, there is a risk that this pattern will persist through adulthood. As an adult, a fatherless daughter is likely to earn a low income, be on social assistance, and experience homelessness.13

Characteristics of Fatherless Daughters:

- Fiercely independent; Strategize to avoid needing or depending on anyone.

- Driven to achieve, to prove their value.

- Conflict avoiders; Try hard to make relationships work (so they are not abandoned again).

- Often sacrifice their own needs to meet others’ needs (so they are appreciated, needed, belong).

- Desire relationships and connection, but experience vulnerability, and struggle to build and maintain relationships.

- May dress/act in ways to get noticed, to “be seen,” and “chosen.” Confuse casual sex with real intimacy; four times more likely to get pregnant as teenagers; inclined to settle quickly in response to deep-seated anxiety and fear no one (more suitable) will ever choose them; they settle because “being with someone is better than being alone.”

- Father Hunger refers to an emptiness experienced by women whose fathers were absent emotionally or physically, a lack of fathering, a yearning for relationship with father than can lead to eating disorders.14 Fatherless girls are twice as likely to suffer from obesity.

- Are inclined to withdraw emotionally and socially; hesitate to express emotions for fear of rejection.

- Tend to protect their privacy; reveal little of themselves.

- Consciously or unconsciously, avoid getting close to people; form superficial relationships.

“Ever since childhood, I’ve built walls around myself. I didn’t open up to people. I didn’t ask about others’ families, jobs, or hobbies. I kept my life private, and I remained socially isolated. These were all self-protective measures so I wouldn’t experience rejection as I did with my dad. Knowing this did nothing to help me change my behavior because my fear of rejection was more powerful than my desire to make connections.”

—McKenna Meyers15

Fathers’ Symptoms following Separation from his Children

There may be underlying false assumptions in society that children are more bonded to their mothers than fathers or that mothers are better caretakers: this is not true. Children and fathers have better mental health the more involved a father is with his child/children after divorce. Whenever possible, it is beneficial to support the father-child connection. Fathers who are separated from their children after divorce feel a deep longing to play a bigger role in their child’s life. (Think of: “Mrs. Doubtfire,” film starring Robyn Williams)

Fathers suffer severe depression and are 2.5 times more likely to commit suicide than married men. Women tend to suffer financial hardship after divorce but are not as likely to commit suicide.16 Children (under 18 years old) who lose a parent to suicide are more likely to develop mental illness and three times more likely to die the same way than kids with living parents. Losing a parent, regardless of cause, increases a child’s risk of committing a violent crime.17.

The separated parents and their extended family may not consider the long-term significance of the father’s absence or decreased contact with the father (figure) on the child’s development. Therefore, after divorce, put aside personal differences and ensure the father maintains his unique role with his daughter and children. The following study found this intention benefited both parents and children.

“Using data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study, researchers examined the association between maternal parenting stress, mother-father relationship status, and fathers’ participation in parenting in terms of engagement, sharing in child-related chores, and cooperative co-parenting. They found that fathers’ engagement with children and sharing in child-related chores reduced maternal parenting stress and that fathers’ participation in parenting was important for both mothers and children even if the mother-father relationship had ended.”18

Right after my father left, my paternal grandfather (and grandmother) who were living with us got up and left; two weeks later, my other grandfather died. So not only did my mother become an overwhelmed single parent, but there were no paternal role models in my life. As a result, as a child, I was afraid and awkward around boys and men—and unconsciously made agreements that followed me through my adult life. I know now, without a doubt, that had one great uncle stepped forward, better agreements would have been made. But at the time, there was little research on the Fatherless Daughter syndrome or how to offset the patterning.

Many factors influence the trajectory of the fatherless daughter syndrome. First is the mother’s capacity to provide a stable, nurturing mother-daughter relationship. Financial stability helps. And inviting an alternative good man—who loves her daughter—to fill that paternal role model, e.g., a grandfather, uncle, or step-father, who will show up regularly, teach skills, participate in, and “see” the daughter growing up. In addition, “help your daughter find some good male role models in other parts of her life. These men may be the fathers of her friends, athletic team coach, a teacher, or a member of your spiritual support group. When she sees how good men behave and interact with her and other people, she will learn how to identify the character traits that define good men.19

Fathers, you matter more than you know! Create a vision of yourself as a father; how you want your daughter to describe you and your relationship after she grows up. Make special Dad-Daughter time to talk about your day, your lives: work and school, and your dreams. Get to know your daughter, and let her know you, too.

The growing body of research on the fatherless daughter syndrome has helped me to understand myself as a fatherless daughter and come to terms with this archetype with more compassion. It is my sincere hope that some of my readers will also find insights and self-compassion.

P.S. Nearing completion of this blog, I put it on hold for a week while I visited Lama Foundation in northern New Mexico. There I witnessed a devoted father’s relationship with his two young daughters; what a timely gift it was to see in action the ideal of what I’d been researching. The father, Maitreya, one of the musicians, was shadowed and adored by his delightful daughters (about nine-years old). I could see he was the first man they knew and loved, he was their trusted role model and teacher. During some sessions they sang and danced with the adults, during others they sat behind him on the wall calmly listening to his teaching. I thought to myself, they don’t have to feel needy or act out to get him to see them; they already know they are the apple of his eye. I predict the even when their future life offers challenges, they will always know they have a Place; and will never struggle with the Fatherless Daughter archetype.

Citations:

- Pedersen, F. A., et al. (1979). Infant Development in Father-Absent Families. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 135(1), 51–62.

- Tori Mora Zangel (2021). The Impact of Fatherlessness on Women Who. Experienced Paternal Abandonment in Early Childhood. Thesis for Pacifica Graduate Institute. p.5. Retrieved from: https://www.proquest.com/openview/28514abc9f248d588d6f070bea5f8abd/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

- Victoria Secunda (1992). Women and Their Fathers. Delacorter Press.

- McKenna Myers (March 7, 2022). Fatherless Daughters: How Growing Up Without a Dad Affects Women. Retrieved from:

https://wehavekids.com/family-relationships/When-Daddy-Dont-Love-Their-Daughters-What-Happens-to-Women-Whose-Fathers-Werent-There-for-Them - Dave Dwyer. (2017). A Psychotherapeutic Exploration of the Effects of Absent Fathers on Children.

https://esource.dbs.ie/bitstream/handle/10788/3317/ba_odwyer_d_2017.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y - Brown, G. L., Mangelsdorf, S. C., & Neff, C. (2012). Father involvement, paternal sensitivity, and father-child attachment security in the first 3 years. Journal of family psychology :

- Tori Mora Zangel, p. 24.

- Carlee Castetter, “The Developmental Effects on the Daughter of an Absent Father Throughout her Lifespan” (2020). Honors Senior Capstone Projects. 50. https://scholarworks.merrimack.edu/honors_capstones/50

- Brown , S. J. (2018). The lived experience of daughters who have absent fathers: A phenomenological study ( dissertation). Journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 26( 3), 421–430. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027836

- Ibid.

- National Fatherhood Initiative®, a 501c3 N.-P. (n.d.). Father Absence Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.fatherhood.org/father-absence-statistic?hsCtaTracking=6013fa0e-dcde-4ce0- 92da-afabf6c53493|7168b8ab-aeba-4e14-bb34-c9fc0740b46e

- Dave O’Dwyer (2017). A psychotherapeutic exploration of the effects of absent fathers on children. https://esource.dbs.ie/handle/10788/331

- A Fathers Impact on Child Development (2018) https://www.all4kids.org/news/blog/a-fathers-impact-on-child-development/

- James Herzog (2001). Father Hunger: Explorations of Adults and Children. Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press.

- McKenna Myers (March 7, 2022). Fatherless Daughters: How Growing Up Without a Dad Affects Women

- A J Kposowa. University California 2000. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jech.57.12.993

- Children Who Lose a Parent to Suicide More Likely to Die the Same Way. (April 21, 2010) Johns Hopkins blog. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/media/releases/children_who_lose_a_parent_to_suicide_more_likely_to_die_the_same_way

- Nomaguchi, K., Brown, S., & Leyman, T. (2017). Fathers’ participation in parenting and maternal parenting stress: Variation by relationship status. Journal of Family Issues, 38, 1132-1156.

- 1Wayne Parker (May 2020). 10 Keys to Raising a Girl without a Father in her Life. https://www.verywellfamily.com/tips-for-raising-a-girl-without-a-father-in-her-life-4126769